WASHINGTON, May 25 (Xinhua) -- A replication study on the famous psychological experiment "marshmallow test" designed to measure children's self-control suggested that the capability to delay one's gratification at a young age might not be as predictive of later life successes as previously thought.

In a study published on Friday in the journal Psychological Science, researchers at New York University's Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development used a larger and more diverse sample of children to reexamine whether the marshmallow test does in fact predict longer-term cognitive and behavioral outcomes.

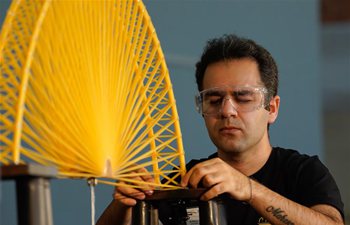

The marshmallow test done in late 1960s and early 1970s by Stanford psychologist Walter Mischel gave children options between one small rewards provided immediately and two small rewards if they waited for about 15 minutes.

Then, Mischel's finding suggested that kid who were able to wait longer for the preferred rewards tend to have better life outcomes, as measured by, for instance, exam scores, academic attainment and body mass index.

Tyler W. Watts, an assistant professor of research and postdoctoral scholar at New York University and his colleagues, however, discovered that while the ability to resist temptation and wait longer to eat the marshmallow or something did predict adolescent math and reading skills, the association was small and disappeared after the researchers controlled for characteristics of the child's family and early environment.

Also, there was no indication that it predicted later behaviors or measures of personality.

Therefore, the researchers concluded that interventions focused only on teaching young children to delay gratification were likely to be ineffective.

"Our findings suggest that an intervention that alters a child's ability to delay, but fails to change more general cognitive and behavioral capacities, will probably have very small effects on later outcomes," said Watts.

"If intervention developers hope to generate the kinds of improvements associated with the original marshmallow study, it is likely to be more fruitful to target the broader cognitive and behavioral abilities related to gratification delay," said Watts.

Watts' team used 918 children, which was a larger sample and geographically diverse dataset.

The researchers also created a subsample based on maternal education and focused much of the analysis on children whose mothers had not completed college by the time the child was born.

This subsample was more representative of the racial and economic makeup of the broader population of children in the United States. By contrast, participants in the original experiments were limited to children from the Stanford University community.

"These new findings should not be interpreted to suggest that gratification delay is completely unimportant, but rather that focusing only on teaching young children to delay gratification is unlikely to make much of a difference," said Watts.